We were up by 7 AM this

morning like the day before. As we were scheduled to board the M.S. Isabella

tonight for the Yangtze River Cruise, we had to pack and check out. Between

that and breakfast, we did not leave for Dazu Grottoes until quarter-to-nine.

The drive to Dazu Grottoes took us through the streets of Chongqing, which

seemed busier today than yesterday. The porters were out in full force, waiting

at street corners for possible customers. Sidewalk vendors hawked their wares

to passersby. Pack horses waited by the side of the road for their loads.

Even the ducks were out, sauntering unhurriedly by the side of the road like

any casual shopper.

As with yesterday's trip, the drive was a series of challenges, with road

construction being the biggest obstacle. Reaching the end of an improved

stretch of pavement generally meant a traverse of several hundred yards of

potholed and washboarded hardpack, complemented here and there by occasional

stretches of sticky red muck. Mom commented that the earth looked just like

the red clay in Georgia. The most unusual addition to today's list of transportation

obstacles relates to the season. Piles of cut rice were spread on the road

in front of many farm houses so that traffic in both directions was pinched

towards the center of the road. According to Mr. Shen, what with the steady

stream of obstacles, it made it easy to pick out the drunk drivers - they

were the ones that drive straight!

We arrived at Dazu Grottoes a bit over two hours later, arriving at 11AM,

and promptly disbursed ourselves from the confines of the minivan. Located

about 90 km away from Chongqing, the Grottoes are tucked away on the side

of a steep hill in the countryside.

Although we had to traverse a large "tourist-trap" area of restaurants and

memento vendors, Mr. Shen took us along a back route that avoided the main

drag (and the most aggressive of the vendors). We soon arrived at a small

plaza where folks were queued up to take electric trams down the last half-mile

or so to the grottoes. As an alternative to the tram, a dozen or so bike-shaws

were sitting around, their owners half-heartedly trying to lure customers

from the tram queue. The problem being, as far as we could see, that the

majority of the tourists there were arriving in large, organized groups,

requiring multiple tram-trips (at 6 to 12 seats per tram), whereas the bike-shaws

had room for two, or perhaps three customers.

A sign in the plaza pointed us to Guangdasi Temple in one direction and to

the Baodingshan Cliffside Carvings on the other. Mr. Shen directed us towards

the Baodingshan Cliffside Carvings. The introduction at the entrance read:

The Cliffside Carvings at Baodingshan were

created under the supervision of Zhao Zhifeng, a famous monk in Southern

Song Dynasty, in more than 70 years from A.D.1174 to 1252. Centreing in Dafowan,

Xiaofowan and stretching 2.5 kilometres in all directions, the nearly 10000

carvings at Baodingshan form a large ritual site of Tantric Buddhism. In

1961, the State Council of China designated the Cliffside Carvings at Baodingshan

to be protected at the national level for historic and cultural value.

Rich in subject matters, grand in scale, excellent

in drawings and texts, the cliffside carvings are a complete system of Buddhist

doctrines. With close attention to the expounding of philosophical principles,

the statues show the integration of the basic doctrines of Buddhism, the

ethics of Confucianism, the theory of Taoism. Displaying the easy words,

the carvings play an important part in encouraging people to do good deeds.

Incorporating the principles of various schools of thinking, they reflect

the characteristics of Buddhist ideology in China's Song Dynasty. Full of

flavour of life and local characteristics, the cliffside carvings are a model

of displaying nationality and life. They vividly reflect that the grotto

art which originated in India completed its process of localization in China.

These carvings tell people the truth of life, arouse their sentiments, captivate

them with Buddhist blessings and happiness or warn them against afterlife

misfortunes and sufferings. The carvings combine scientific principles with

plastic art. They are an epitome of grotto art.

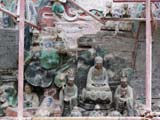

Walking through the main site, we were awed by the span and

magnificence of the cliffside carvings. The carvings were divided into various

niches with themes centering around Buddhist doctrines, filial piety, and

punishment in hell of the most painful sort for sinners.

The first niche we came to was the "Ritual Site of Liu Benzun". Liu Benzun

was a lay buddhist from Leshan in Sichuan Province in the late Tang Dynasty.

He was reputedly the first patriarch of Esoteric Buddhism in Sichuan Province

and the founder of a peculiar religious movement which stressed the use of

mantras (incantations) and self-mutilations for the welfare of his followers.

Legend has it that he successively amputated and burned ten parts of his

body. Although described as a "lay" buddhist, part of his niche featured

statues of his attendants.

Next was "Niche of the Nether World". In the middle of the niche sat Ksitigarbha,

flanked by 10 Boddhisattvas, the God of Present-life Reward, and the God

of Quick Reward. Legend has it that Ksitigarbha vowed to not achieve Buddhahood

until "all the Hells are empty". Quoting from Yuli - The Holy Book:

With my compassionate vows, I came to succor

all the sentient beings in this spiritual realm. Unfortunately, more people

did bad than good. People came and gone, and there is no end to my salvation.

What good methods must I use so that all human beings will believe in the

law of karma, repent their wrong doings, start doing good deeds, and distance

themselves from the endless cycle of transmigration between life and death?

Only by doing so, will human beings not fall into the nether world again.

And those who are already suffering in this realm can be uplifted to a higher

level by virtue of their descendants' merits .... For those who have made

severe mistakes in life and have vowed not to repeat the same mistakes, and

have since started to do good deeds, to show repentance, their punishments

in hell will be reduced and amnesty is given. As for those whose merits equate

their demerits, no punishment will be meted out.

The lower part of the niche depicted 18 graphic scenes of

sinners being tortured in various hells, including "the Knife mountain and

the Knee-chopping hells".

The theme of the next set of carvings was "Sakyamuni's Filial Piety". A large

statue of Sakyamuni sat in the middle of the niche. Surrounding the center

bust were various carvings depicting Sakyamuni practicing Buddhism and showing

his filial piety in previous lives. One carving showed a filial son carrying his legless parents

in baskets balanced from a bamboo pole on his shoulder while he begged for

alms. In the carving, both his parents had a piece of bread in their hands.

The son had another piece of bread tucked in his belt. The story is that

instead of eating the extra bread, the filial son saved the bread for his

parents' next meal. These stories were designed to tug at the heartstrings

although not so much at the common sense. The filial son would have fared

better leaving the parents at home so he would have had more energy to hunt

for bread. (And Ting is heretofore condemned to the Knee-chopping hell for

this astute but unfilial observation).

Seven Buddhas sat in the upper tier of the "Niche of Parental Love Sutra".

The lower tiers of the niche depicted scenes of "parental love in bringing

up children with plots linking to each other as (in) a picture book". The

dominant message was the depiction of the sacrifices made by parents in bringing

up their children. In return, the children should repay the parents with

acts of filial duty.

The "Reclining Buddha", one of the most famous carvings at Dazu Grottoes,

stretched the length of the next niche. According to legend, this scene represents

the Buddha on his deathbed giving instructions to his 12 disciples.

The next sight was a cave in which resided the Goddess of Mercy with a Thousand

Hands and Eyes. We were not allowed to take pictures here, but you can see

glimpses of the statue through the holes in the cave through which we took

pictures. Legend has it that when her father fell ill, she plucked out her

eyes and sliced flesh from her arm to use as ingredients for a medicine that

saved his life. To show his gratitude he ordered a statue erected in her

honor telling the sculptor to make the statue "quanshou quanyan" meaning

"with completely formed arms and eyes." The sculptor misunderstood the father

as saying "qianshou qianyan" (that is the problem with having the different

dialects in China) and made the sculpture with "a thousand arms and eyes."

From that day on, the Goddess of Mercy has been represented with a thousand

arms and a thousand eyes.

The next niche featured the "Three Saints of Huayan School of Buddhism".

Three large statues of the Buddhist deities loomed over the niche: Vairocana

Buddha in the middle, Manjusri Bodhisattva on the right of Vairocana, and

Samantabhadra Bodhisattva on the left. The statues reached 23 feet in height.

The pagoda alone held in the hand of Manjusri purportedly weighed close to

half a ton!

Next, the "Niche of Grand Precious Garret" featured three Buddhists sitting

in Zazen under a black bamboo grove. The significance of this niche escaped

us except for the fact that Du Xiaoyan, deputy minister of the Ministry of

War in Song Dynasty of China, wrote the three Chinese characters prominent

in the middle of the niche.

Finally, The "Niche of Guardians of Buddhist Law" featured the nine guardians

whose duty was to "guard the ritual site and subdue monsters".

Coming out of Dazu Grottoes, Randy had expected to visit Guangdasi Temple

next. To his disappointment, we were all unceremoniously ushered into the

van and chauffeured to the Dazu Hotel for lunch.

|

|